If you have been watching at the 4G ads surrounding us lately, medicine the number 150 Mbps must sound familiar to you. This is the download speed we are supposed to reach from now on if we jump into 4G.

However, as it usually happens with these matters, that is the system maximum theoretical speed, only reachable if the maximum bandwidth (20 MHz) is available, we are alone at the network and our mobile phone belongs to a specific category.

Unfortunately, it is quite difficult to accomplish these conditions simultaneously, and that’s why we will try to approach a more realistic speed depending on these features. There are a lot of features indeed that influence the download and upload speed we experiment. Of course, the network load will make it change significantly, but we leave this analysis, a lot more complex, for future posts.

For a start, we will suppose that the device has all the radio resources for itself for the following speed values shown. In this situation there are two things that affect in a direct way to the speed decrease: the LTE device category and the bandwidth that our 4G provider has available. Let’s have a brief look at them:

• LTE device categories

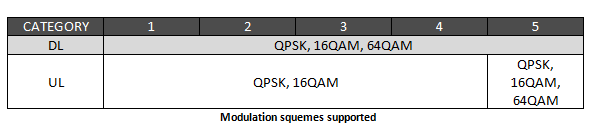

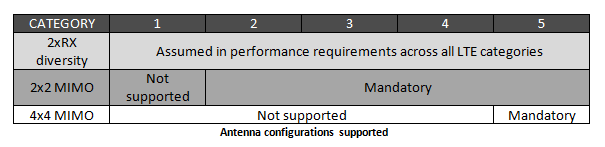

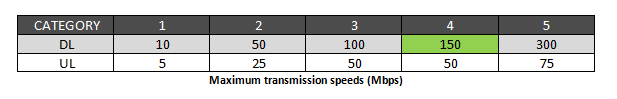

There are five different LTE UE categories (UE stands for User Equipment). They are needed to ensure that the base station, or eNodeB, can communicate correctly with the user equipment. By relaying the LTE UE category information to the base station, it is able to determine the performance of the UE and communicate with it accordingly. The following tables show the supported features for the five categories and the maximum speeds reachable for each of them:

The modulation that provides the highest speed is 64 QAM, as it sends more information per symbol; but the fact that it can or cannot be used depends on the radio channel instant state. We suppose this modulation is been used for the given speed values (if the device category supports it).

The more TX and RX antennas (MIMO) are used, the bigger speed. However it is quite probable that the device only supports a 2×2 MIMO squeme.

According to the antenna configuration, the maximum download speed in shown in the next table:

It is not until Category 4 when we can reach the famous 150 Mbps, and we could get even twice that speed with Category 5, though this speed is not advertised because on the standard LTE deployments being made in Spain, 2×2 MIMO is used.

It is also worth noting that UE class 1 does not offer the performance offered by that of the highest performance HSDPA category.

(All categories for a 20 MHz bandwidth).

The category our LTE device belongs to is something that could easily not be taken into account, and however will condition significantly its performance. High range devices available nowadays such as Iphone 5 or Samsung Galaxy S4 are Category 3 devices. Huawei has presented on march 2013 the Pocket Wi Fi LTE GL04P that has among its features been the world’s first 4G LTE Category 4 User Equipment.

LTE UE categories are defined in the 3GPP specification “3GPP TS 36.306 Evolved Universal Terrestrial Radio Access (E-UTRA); User Equipment (UE) radio access capabilities (Release 8)”.

• LTE Bandwidth

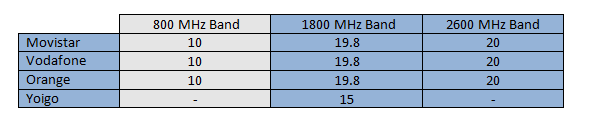

The configured bandwidth defines and limits the amount of physical resources that carry the information scheduled to the phone. The maximum configurable bandwidth in LTE is 20 MHz, but network providers may not use all of it, but 5, 10 or 15 MHz. So if we want to know the speed we can reach when we choose a provider, we should also know the bandwidth it is been using.

At the present moment, the spectrum distribution in Spain for the four LTE operators is as follows (the 800 MHz band is not yet available for LTE):

Even though they bought the license for 20 MHz, it is possible that it is not fully used at the beginning and so be extended in the future as the number of users increases. So this could be another possible reason for our speed falling.

Anyway if we supposed the 20 MHz are used, and also the best channel quality (that is 64 QAM), the maximum download and upload speeds for each category are as follows:

In order to have a reference, the 100 Mbps we get for a category 3 device and 20 MHz, fall to 79 Mbps with 10 MHz and to 39 Mbps with 5 MHz.

Therefore, we see that in the best situation, the 150 Mbps have fallen to 100 Mbps if we have a category 3 device. Starting with these 100 Mbps we will then have to take into account that we are not alone at the network and we have to share the resources with others users. Measurements taken in slightly loaded scenarios show peak rates between 50 and 70 Mbps as best performances at places where the coverage was maximum.

Even though the facts we have been discussing , with LTE we will experience better rates and much lower delays than with the previous HSDPA technology, but we have to take into account that those 150 Mbps are, at the moment at least, an utopia.

Published originally in http://intotally.com/tot4blog/ by Leticia Almansa López (contact)